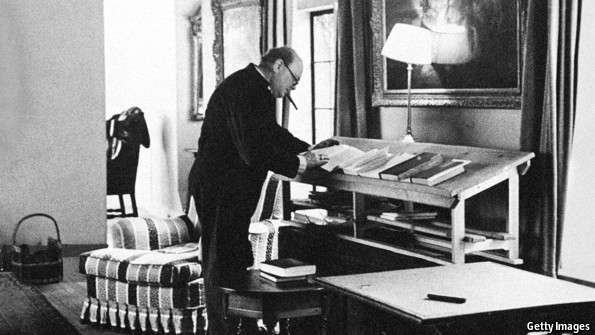

Winston Churchill knew it. Ernest Hemingway knew it. Leonardo da Vinci knew it. Every trendy office from Silicon Valley to Scandinavia now knows it too: there is virtue in working standing up. And not merely standing. The trendiest offices of all have treadmill desks, which encourage people to walk while working. It sounds like a fad. But it does have a basis in science.

Sloth is rampant in the rich world. A typical car-driving, television-watching cubicle slave would have to walk an extra 19km a day to match the physical-activity levels of the few remaining people who still live as hunter-gatherers. Though all organisms tend to conserve energy when possible, evidence is building up that doing it to the extent most Westerners do is bad for you—so bad that it can kill you.

That, by itself, may not surprise. Health ministries have been nagging people for decades to do more exercise. What is surprising is that prolonged periods of inactivity are bad regardless of how much time you also spend on officially approved high-impact stuff like jogging or pounding treadmills in the gym. What you need instead, the latest research suggests, is constant low-level activity. This can be so low-level that you might not think of it as activity at all. Even just standing up counts, for it invokes muscles that sitting does not.

Researchers in this field trace the history of the idea that standing up is good for you back to 1953, when a study published in the Lancet found that bus conductors, who spend their days standing, had a risk of heart attack half that of bus drivers, who spend their shifts on their backsides. But as the health benefits of exercise and vigorous physical activity began to become clear in the 1970s, says David Dunstan, a researcher at the Baker IDI Heart & Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, Australia, interest in the effects of low-intensity activity—like walking and standing—waned.

Arse longa, vita brevis

Over the past few years, however, interest has waxed again. A series of epidemiological studies, none big enough to be probative, but all pointing in the same direction, persuaded Emma Wilmot of the University of Leicester, in Britain, to carry out a meta-analysis. This is a technique that combines diverse studies in a statistically meaningful way. Dr Wilmot combined 18 of them, covering almost 800,000 people, in 2012 and concluded that those individuals who are least active in their normal daily lives are twice as likely to develop diabetes as those who are most active. She also found that the immobile are twice as likely to die from a heart attack and two-and-a-half times as likely to suffer cardiovascular disease as the most ambulatory. Crucially, all this seemed independent of the amount of vigorous, gym-style exercise that volunteers did.

Correlation is not, of course, causation. But there is other evidence suggesting inactivity really is to blame for these problems. One exhibit is the finding that sitting down and attending to a task—anything from watching television to playing video games to reading—serves to increase the amount of calories people eat without increasing the quantity that they burn. Why that should be is unclear—as is whether low-level exercise like standing would deal with the snacking.

A different set of studies suggests that simple inactivity by itself—without any distractions like TV or reading—causes harm by altering the metabolism. One experiment, in which rats were immobilised for a day (not easy; the researchers had to suspend the animals’ hind legs to keep them still) found big falls in the amount of fats called triglycerides taken up by their skeletal muscles. This meant the triglycerides were available to cause trouble elsewhere. The rats’ levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) fell dramatically as well. HDL is a way of packaging cholesterol, and low levels of it promote heart disease. Other studies have shown the activity of lipoprotein lipase—an enzyme that regulates levels of triglycerides and HDL—drops sharply after just a few hours of inactivity, and that sloth is accompanied by changes in the activity levels of over 100 genes.